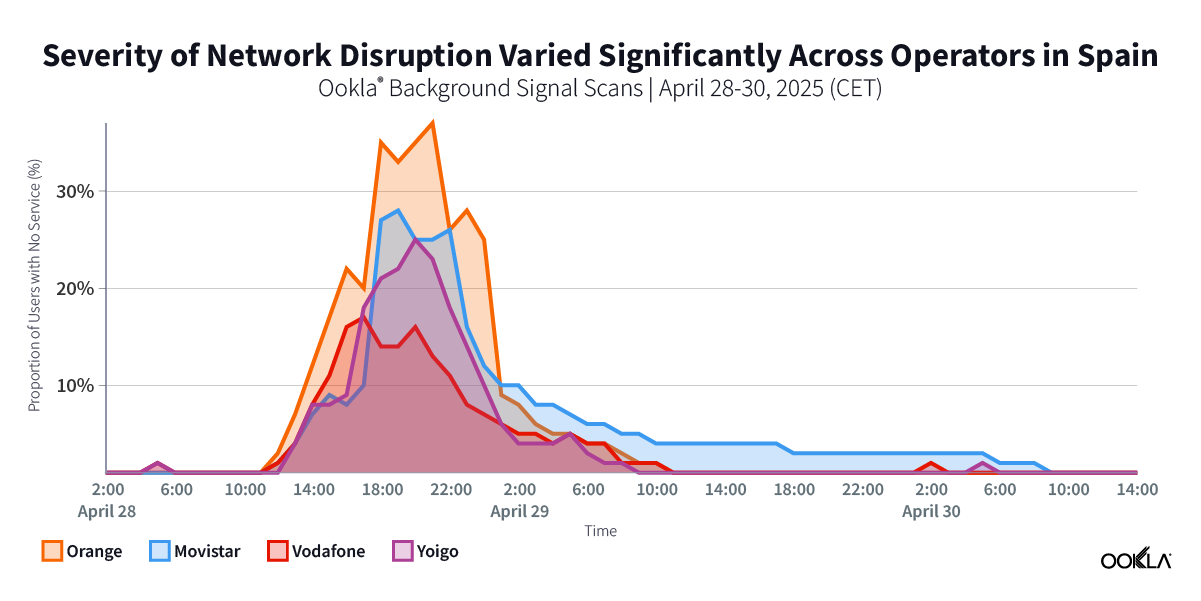

Robust power redundancy markedly reduced outage impacts for one operator, while limited backup systems led to widespread service collapse for another, highlighting the importance of resilience planning and investment.

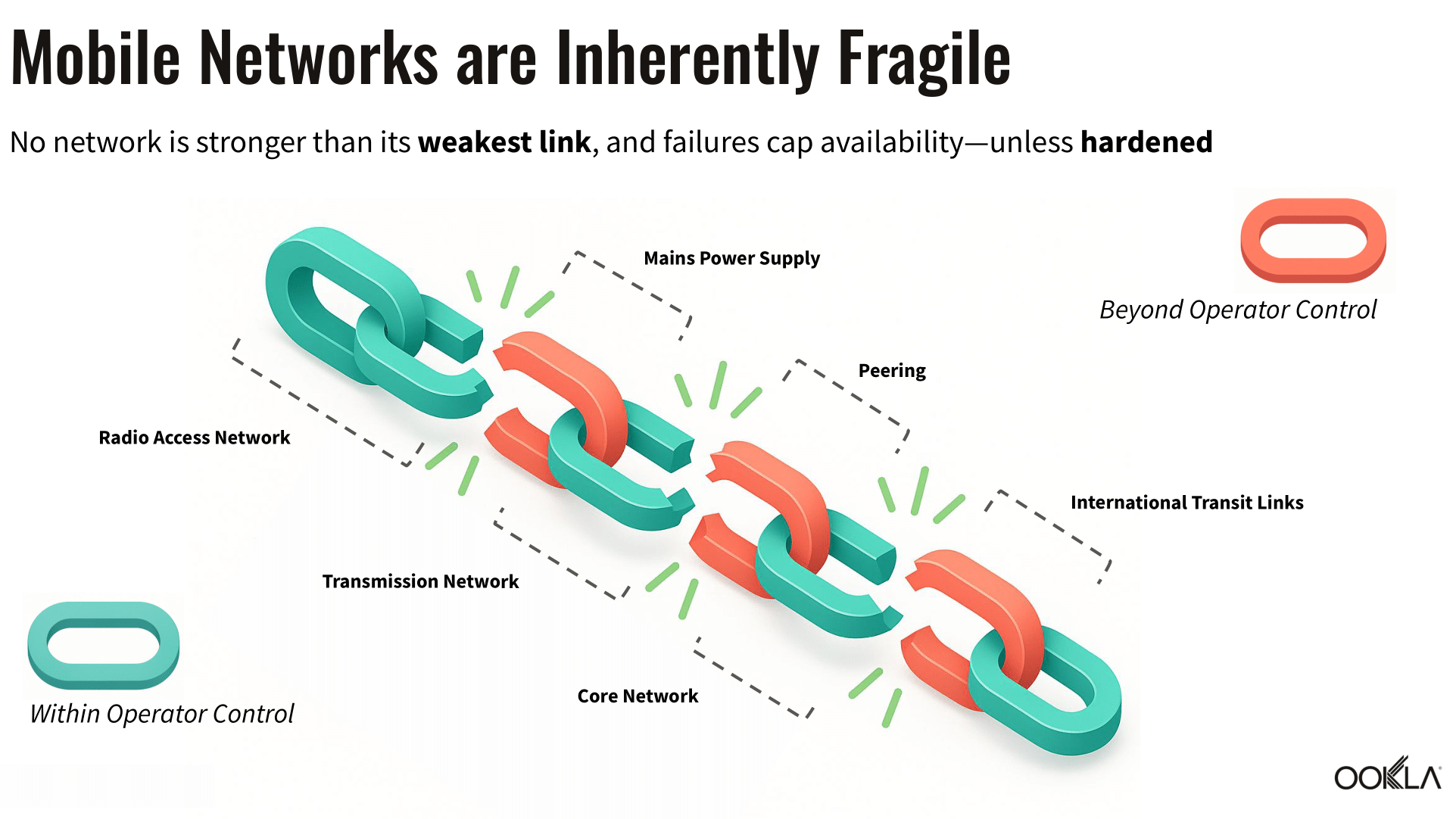

Mobile operators, equipment vendors, and policymakers throughout Europe are grappling with the challenge of hardening telecom infrastructure to withstand increasingly frequent and severe disruptions caused by power outages, sabotage, and extreme weather events.

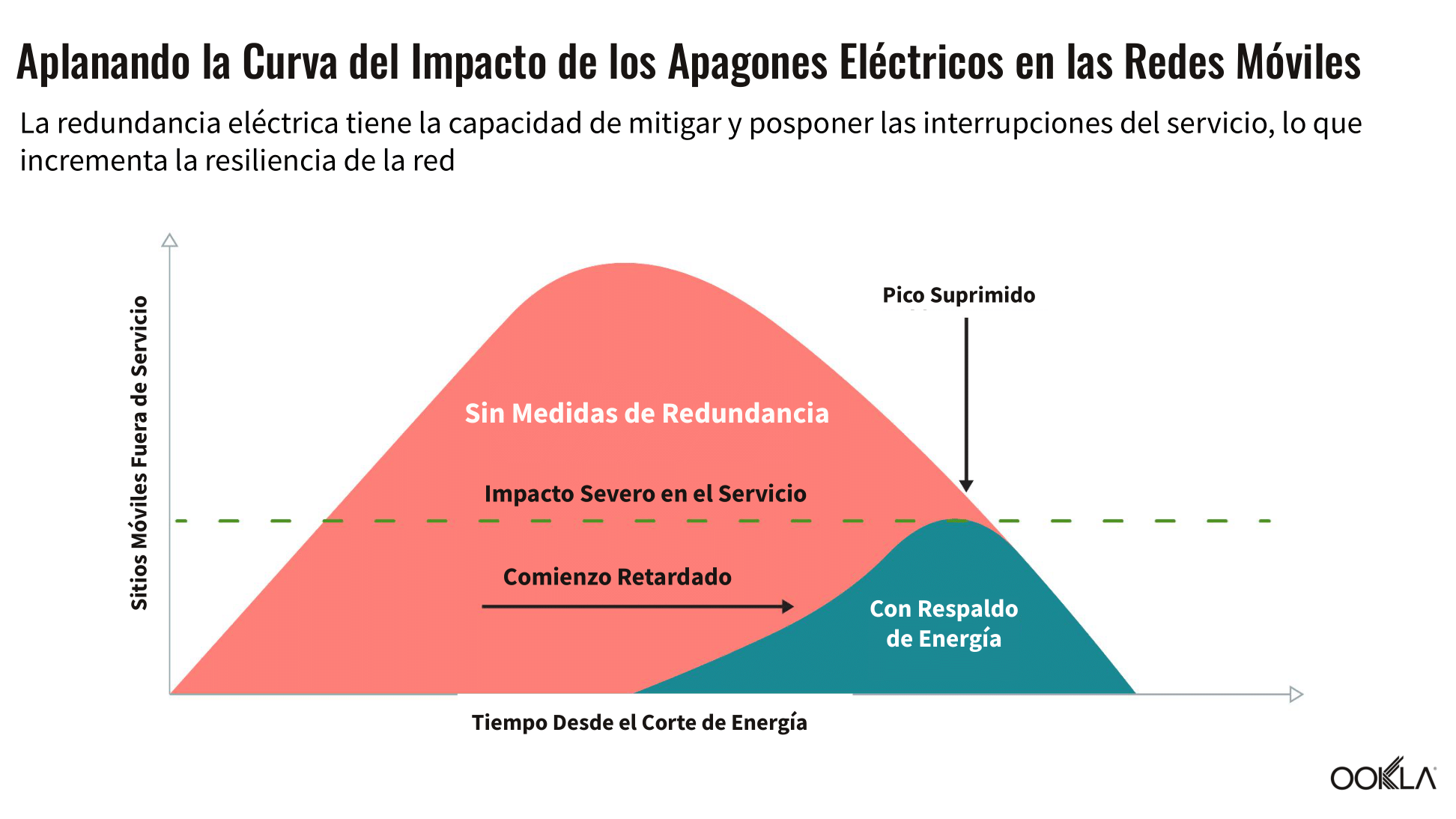

Earlier this year, the Iberian grid blackout placed Portugal’s mobile operators at the coalface of this resilience challenge, creating a real-world stress test of their infrastructure on an unprecedented scale. Effective power redundancy, supported by battery and generator backups, coupled with energy conservation measures that strategically adjusted network configurations to preserve site availability, emerged as critical tools for limiting outage impact.

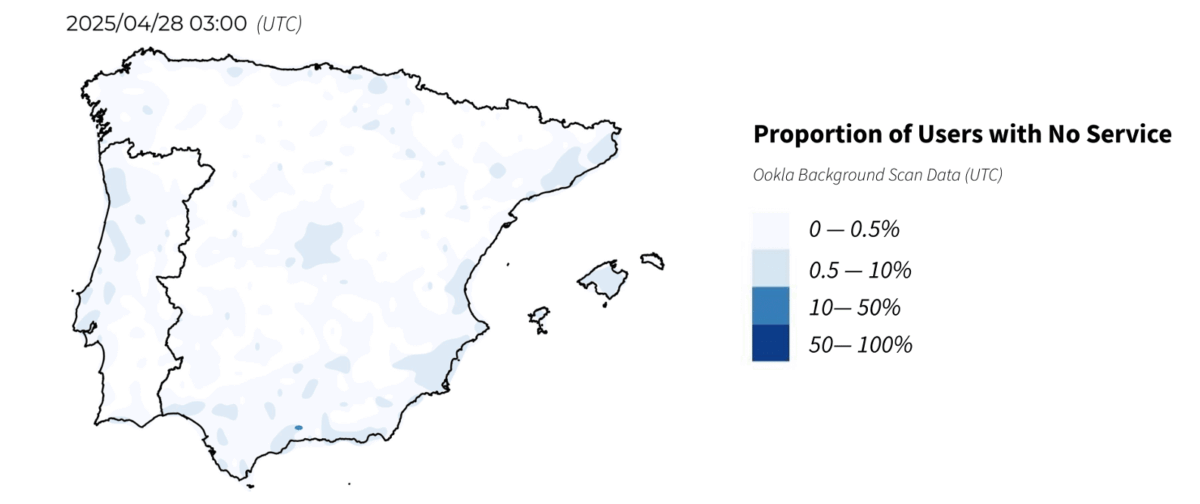

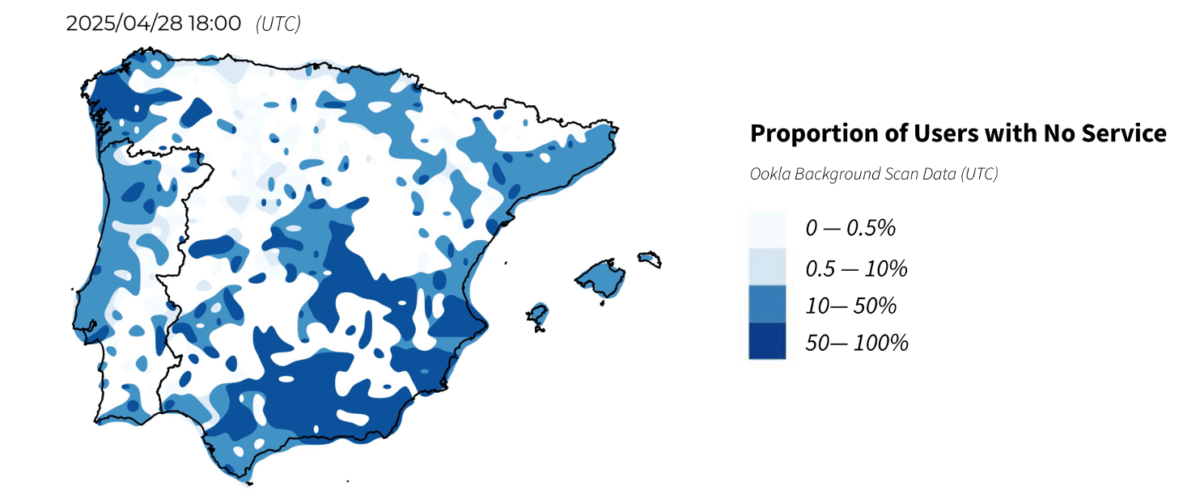

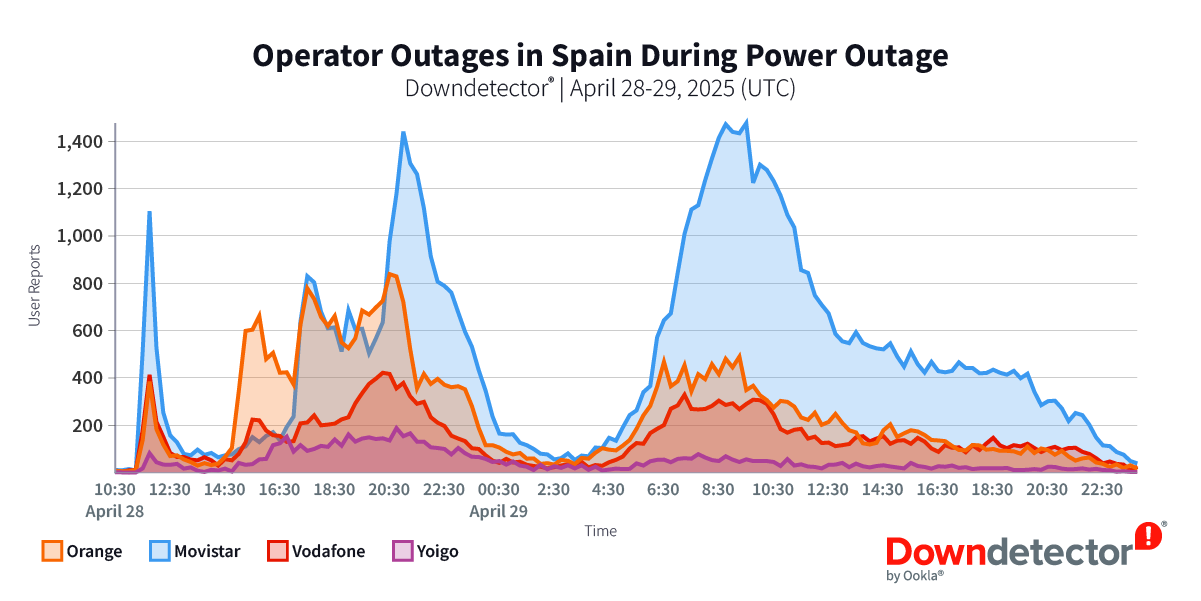

However, new analysis of Ookla® background signal scan data from the outage reveals that each operator’s ability to mitigate the disruption varied significantly, offering important lessons for future improvements in Portugal and beyond. This research builds upon our earlier findings in Spain, where we cross-referenced crowdsourced ‘no service’ data with satellite imagery to demonstrate that the profile of network disruptions and recovery moved in lockstep with power grid developments.

Key Takeaways:

- At the height of the network disruptions on the evening of April 28th, more than one in three mobile network users in Portugal was left without service. The voltage drop triggered by the grid collapse rapidly cascaded through Portugal’s mobile networks, driving the share of users experiencing total service loss (unable to call, text, or use data as sites went dark) from a pre-blackout baseline below 0.1% to over 10% within two hours. At the peak late on April 28th, as battery and generator backups were progressively depleted, more than 60% of users across the worst-affected areas of Portugal were left without service.

- While severe network outages affected all Portuguese operators during the blackout, mobile users on DIGI’s network were significantly more likely to experience a total loss of service. With up to 90% of DIGI subscribers left without any mobile coverage for over twenty-four hours, the outage exposed critical gaps in redundancy across multiple infrastructure layers, from mobile sites at the edge all the way to the core, potentially reflecting the limitations of DIGI’s less mature network buildout in Portugal.

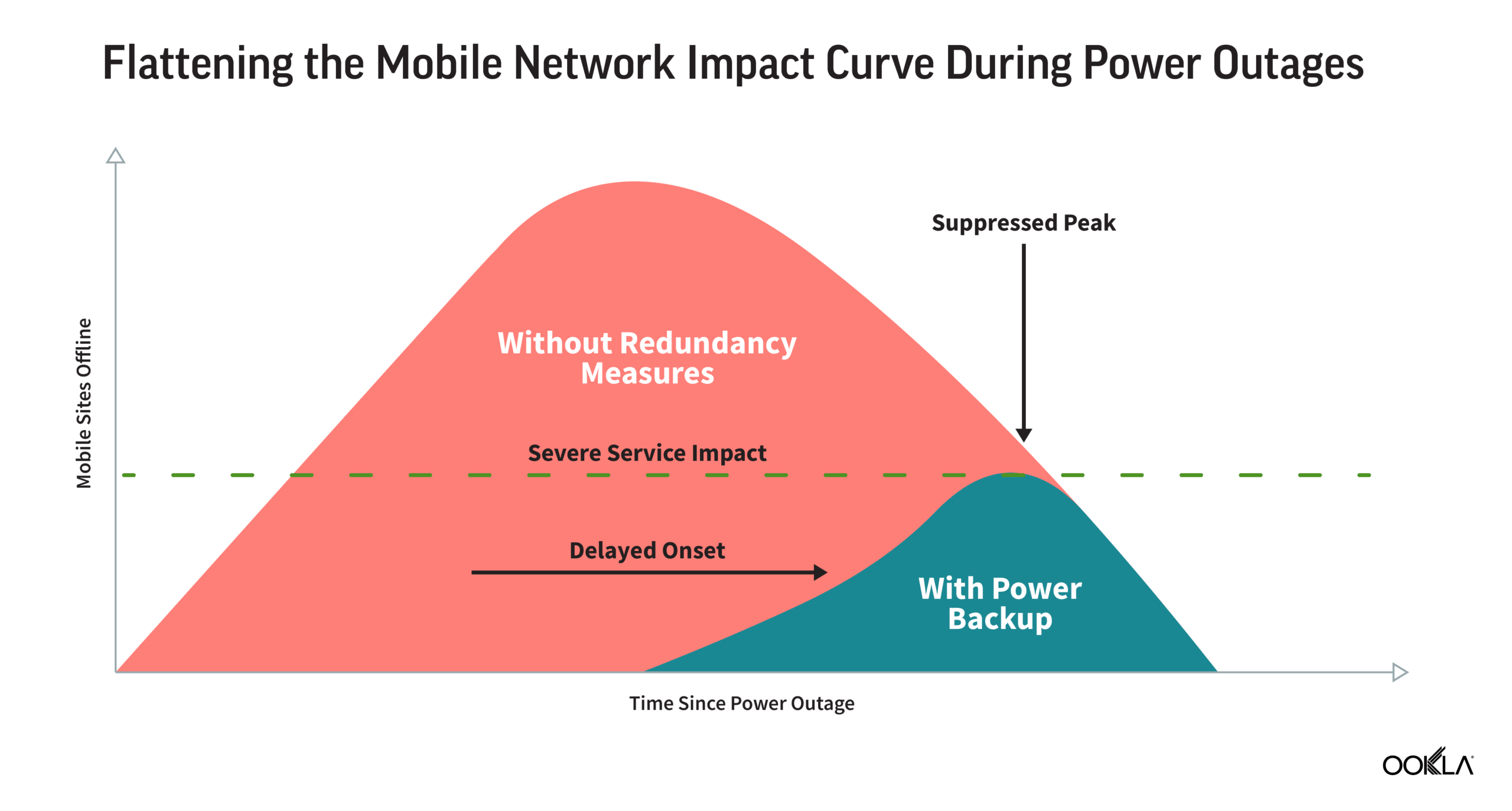

- MEO’s network demonstrated significantly greater resilience across Portugal during the April 28th blackout, illustrating how deep and widely deployed battery reserves can materially flatten and delay outage impacts triggered by power loss. At the peak of service disruption six to eight hours after the power loss, MEO’s subscribers were on average half as likely to lose service as those on NOS’s network, four times less likely than Vodafone’s subscribers, and six times less likely than DIGI’s. As a result, at least tens of thousands more MEO subscribers likely stayed connected for calls, texts, and data throughout April 28th.

- The variation in outage impact between operators in Portugal was significantly greater than in Spain, revealing much deeper asymmetry in the level of power resilience across Portugal’s mobile networks. As in Spain, however, the pattern of service restoration reflected the geographically phased re-energisation of the power grid, with network disruptions persisting later into the night in Lisbon than in Porto, consistent with transmission operator REN’s blackstart process, which began in the north and moved south.

Blackout cascaded through Portugal’s mobile networks, forcing aggressive energy conservation measures as traffic demand surged and power backups were depleted

When the grid-wide collapse severed power to virtually all of mainland Portugal at 11:33 local time on April 28th, mobile sites were immediately forced off mains electricity and had to rely on batteries or generator backups, triggering a nationwide race between grid restoration and the exhaustion of backup reserves across telecom networks. Sites lacking any power autonomy vanished immediately (such as dense urban small cells), triggering a stepwise collapse in overall network density that resembled a cliff drop followed by a gradually declining tail.

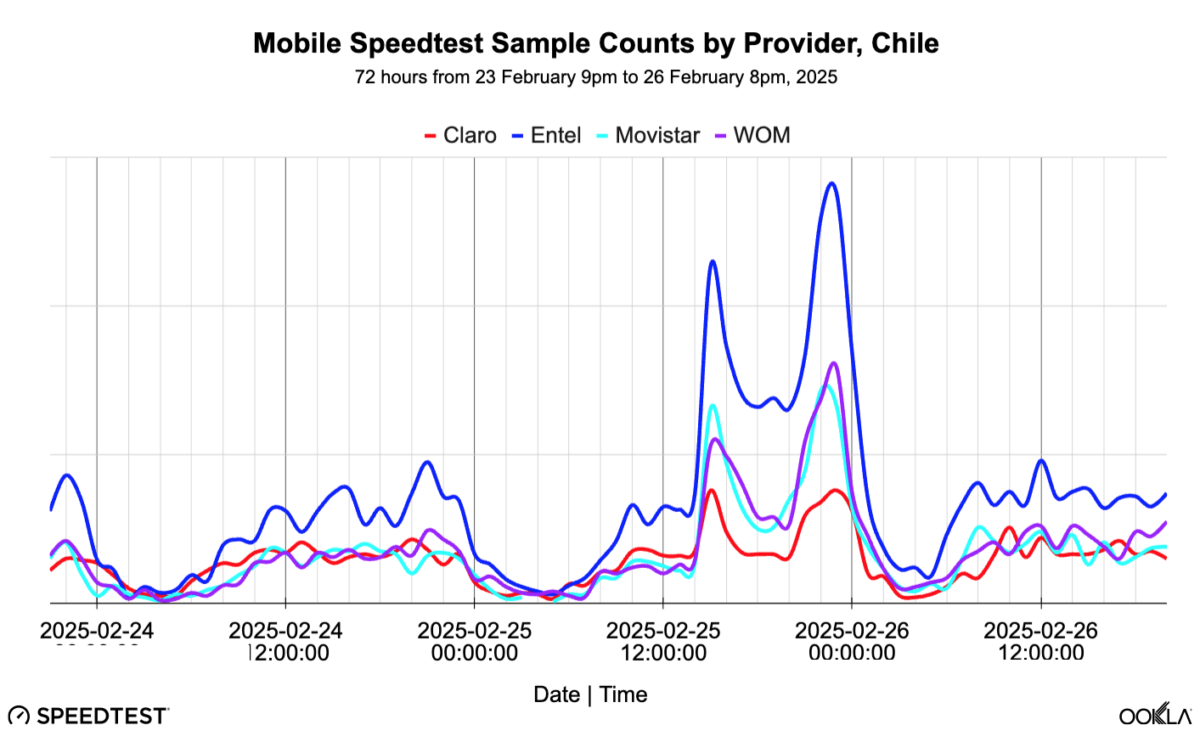

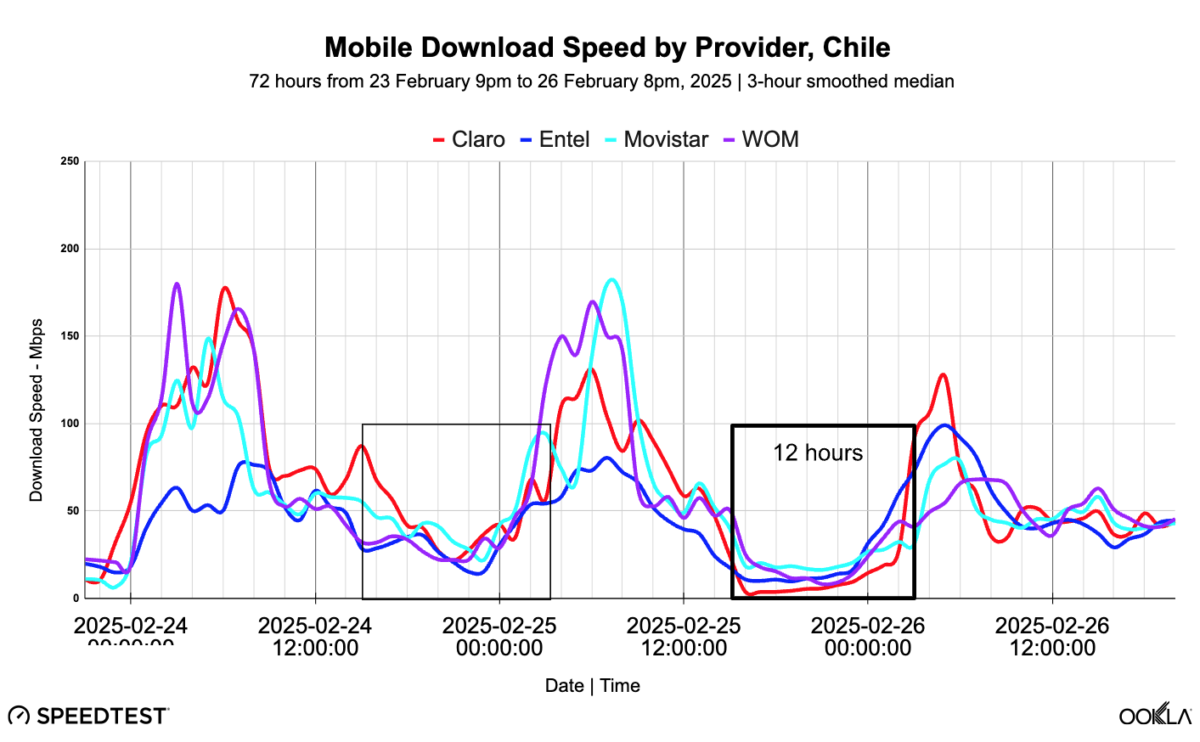

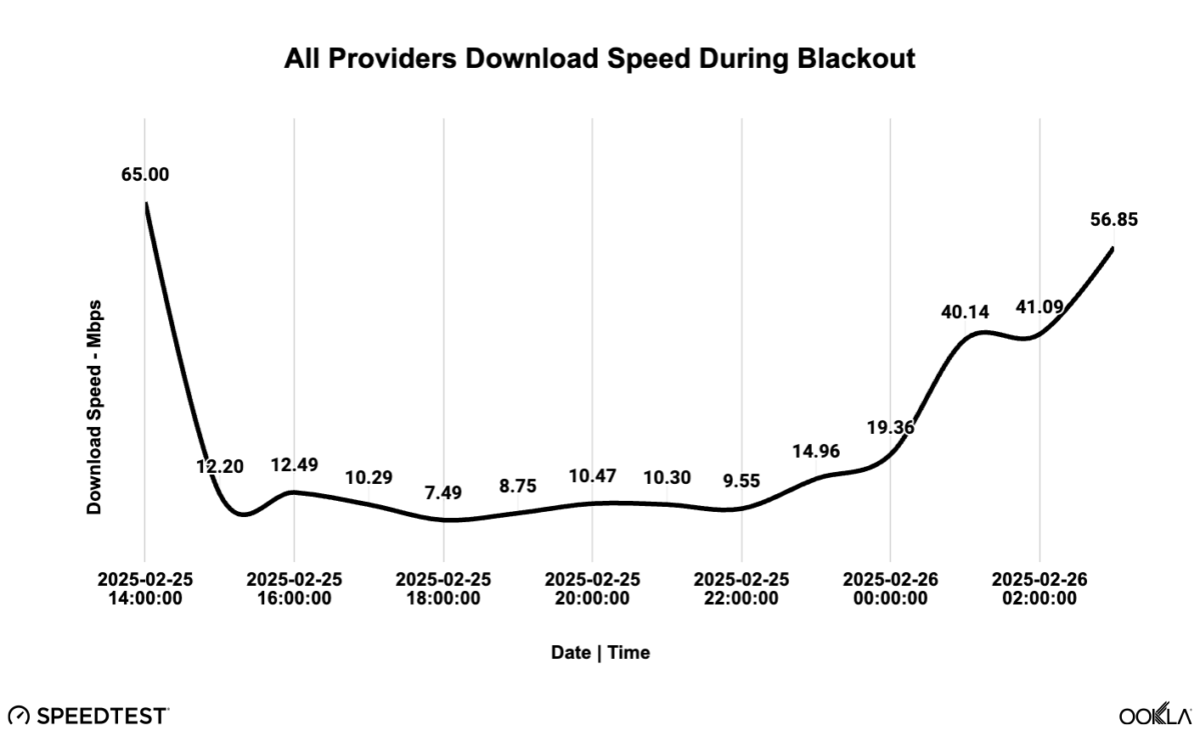

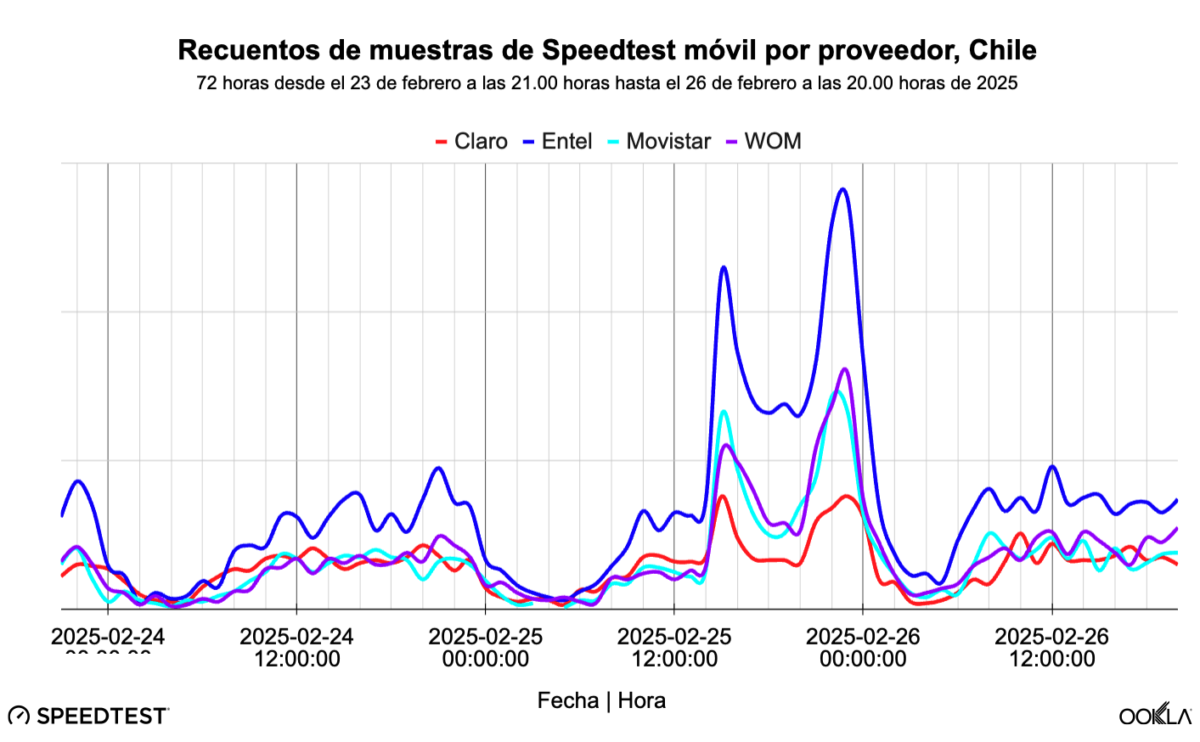

The sudden loss of residential electricity rendered fixed networks and in-home Wi-Fi CPEs unusable, forcing users onto mobile networks and unleashing a massive surge in traffic that put intense pressure on capacity, particularly in urban areas. This was reflected in a rapid degradation of mobile network performance across all metrics, as illustrated in analysis of Speedtest Intelligence® data published in our earlier research.

The spike in demand on the country’s mobile infrastructure occurred just as operators were racing to implement aggressive energy conservation measures to extend the life of backup power at mobile sites. These efforts included phased 5G switch-offs (as 3.5 GHz massive MIMO radios typically draw two to three times the power of a low-band 4G sector), prioritizing core voice and text services, and reducing cell-edge transmit power where network loads were light.

Blackout produced a composite outage curve made of one large step (DIGI) superimposed on several peaked pulses (Vodafone, NOS, and MEO)

Although all of Portugal’s mobile operators implemented similar energy conservation measures during the blackout, the depth and distribution of power autonomy within each operator’s site portfolio, including the partially shared footprint between NOS and Vodafone, ultimately shaped their network resilience. This is evident in the distinct outage trajectories revealed by analysis of background signal scan data, which shows whether a device could connect to any network (2G, 3G, 4G, or 5G) based on a very large, geographically diverse sample across Portugal.

DIGI’s still-nascent network, which is leaner and heavily concentrated in cities (therefore making deployment of power autonomy more challenging at space-constrained rooftop sites), proved particularly brittle. Within four hours of the voltage drop, the share of subscribers on its network with no signal shot up from less than 0.1% to more than 90%, a classic step-function collapse. The operator’s entire radio layer appeared to disappear almost simultaneously, driven by shallow site-level batteries and little layered fallback. In addition, network access remained crippled for more than a day, likely pointing to a catastrophic failure of deeper elements such as the Evolved Packet Core (EPC) in Lisbon, which may have lacked geo-redundancy or sufficient power autonomy.

While Vodafone’s outage curve did not exhibit the same cliff-like profile as DIGI’s, instead following more of a triangular or peaked pulse shape, it still reached a very sharp peak. The heterogeneous distribution of backup power across Vodafone’s site footprint produced a multi-step survival curve, with each autonomy band expiring (for example, sites with four-hour batteries) causing another visible kink in the aggregate outage trajectory.

By 19:30 local time, almost 70% of Vodafone’s subscribers were left without service as the last reserves of backup power began to deplete ahead of grid restoration. While this was still materially lower than the more than 90% service loss seen on DIGI’s network in Portugal, it was nearly twice as high as the peak outage experienced by any operator in Spain on April 28th. Service was, however, rapidly restored on Vodafone’s network from 20:00 in a phased geographic sequence, aligning with the restoration of the grid, with the no service ratio falling below 5% by midnight.

Unlike other operators in Portugal, Vodafone and NOS have extensive RAN sharing, with a joint venture owning and operating actively shared sites in rural and interior areas, while sites in urban areas are passively shared. Despite this, the outage profile for NOS was notably less severe. This indicates that NOS’s network features relatively deeper power resilience in locations where its infrastructure is not actively shared, compared with Vodafone’s independently managed sites. On NOS’s network, the proportion of subscribers without service peaked early at nearly 30%, closely resembling the impact profile of the worst-affected operator in Spain, and remained at this level until power was restored.

The merits of widely deployed and deep battery reserves in flattening and delaying the outage curve (much like masks and vaccines suppress infection spread during a pandemic) were clearly demonstrated in MEO’s case. Its outage peak was lower and the tail shorter, with the proportion of subscribers left without service peaking at just over 16%, which was the best performance observed across Spain and Portugal on April 28th.

Outage experience demonstrates the role of power autonomy and geo-redundancy in hardening telecom infrastructure against external shocks

When the grid collapsed, every Portuguese operator reached for the same first lever by killing off the power-hungry 5G layer, but what happened next diverged. The breadth and depth of each operator’s power autonomy (at the site level) and the extent of geo-redundancy (at the core level), along with their ability to cascade lower-band layers, throttle traffic, and reshuffle spectrum, dictated how much of their network stayed online and for how long during the blackout.

The pronounced asymmetry in outage impacts observed across operators’ subscriber bases highlights the urgent need to harden mobile networks and raise all infrastructure layers to a higher baseline of resilience ahead of future severe events. There is now broad consensus, which is expected to be enshrined in the European Commission’s forthcoming Digital Networks Act (DNA), that telecom networks are critical infrastructure essential for societal functioning, and that even brief service disruptions can quickly escalate into serious public safety risks.

Da vulnerabilidade à resiliência: Como as redes móveis portuguesas reagiram ao apagão na Península Ibérica

Uma forte redundância energética atenuou significativamente os efeitos da falha para um dos operadores, enquanto a escassez de sistemas de reserva provocou a interrupção generalizada dos serviços noutro, evidenciando a importância do planeamento e do investimento em resiliência.

Os operadores móveis, fornecedores de equipamentos e reguladores em toda a Europa estão a enfrentar o desafio de reforçar a infraestrutura das telecomunicações para resistir a interrupções cada vez mais frequentes e graves causadas por falhas de energia, sabotagem e fenómenos meteorológicos extremos.

No início deste ano, o apagão da rede ibérica colocou os operadores móveis portugueses na linha da frente deste desafio de resiliência, criando um teste real de resistência das infraestruturas numa escala sem precedentes. A redundância energética eficaz, apoiada por baterias e geradores de reserva, aliada a medidas de poupança de energia que ajustaram estrategicamente as configurações da rede para preservar a disponibilidade dos sites, revelou-se uma ferramenta crucial para limitar o impacto das falhas de energia.

No entanto, uma nova análise dos dados de monitorização passiva de sinal da Ookla® durante a falha revela que a capacidade de cada operador para mitigar a interrupção variou significativamente, oferecendo lições importantes para futuras melhorias em Portugal e além-fronteiras.

Esta investigação baseia-se nas conclusões anteriores obtidas em Espanha, onde cruzámos dados crowdsourced de “sem serviço” com imagens de satélite para demonstrar que o perfil das perturbações e da recuperação das redes evoluiu em paralelo com a situação da rede elétrica.

Principais conclusões:

- No auge das perturbações na rede, na noite de 28 de abril, mais de um em cada três utilizadores de redes móveis em Portugal ficou sem serviço. A queda de tensão desencadeada pelo colapso da rede elétrica propagou-se rapidamente nas redes móveis do país, fazendo com que a proporção de utilizadores com perda total de serviço (sem possibilidade de fazer chamadas, enviar mensagens ou utilizar dados, à medida que os sites ficavam inoperacionais) subisse de um valor inferior a 0,1 % antes do apagão para mais de 10 % em menos de duas horas. No pico, já no final do dia de 28 de abril, à medida que as baterias e os geradores de reserva se esgotavam progressivamente, mais de 60 % dos utilizadores nas zonas mais afetadas de Portugal ficaram sem serviço.

- Embora todas as operadoras portuguesas tenham sido afetadas por graves falhas na rede durante o apagão, os utilizadores móveis da rede DIGI foram significativamente mais propensos a experienciar uma perda total de serviço. Com até 90 % dos assinantes da DIGI sem qualquer cobertura móvel durante mais de vinte e quatro horas, a falha expôs lacunas críticas na redundância em vários níveis da infraestrutura, desde as antenas móveis na periferia até ao núcleo da rede, refletindo potencialmente as limitações do desenvolvimento menos amadurecido da rede da DIGI em Portugal.

- A rede da MEO demonstrou uma resiliência significativamente maior em todo o território português durante o apagão de 28 de abril, mostrando como as reservas robustas e amplamente implantadas de baterias podem atenuar e atrasar de forma significativa os impactos das falhas de energia. No pico da interrupção do serviço, entre seis e oito horas após a perda de energia, os assinantes da MEO tinham, em média, metade da probabilidade de perder o serviço comparativamente aos da NOS, quatro vezes menos do que os da Vodafone e seis vezes menos do que os da DIGI. Como resultado, provavelmente dezenas de milhares de assinantes da MEO mantiveram-se conectados para chamadas, mensagens e dados ao longo de todo o dia 28 de abril.

- A variação do impacto das interrupções entre operadores em Portugal foi significativamente maior do que em Espanha, revelando uma assimetria muito mais profunda no nível de resiliência energética das redes móveis portuguesas. No entanto, tal como em Espanha, o padrão de restabelecimento do serviço refletiu a reenergização faseada geograficamente da rede elétrica, com as perturbações a persistirem até mais tarde durante a noite em Lisboa do que no Porto, em conformidade com o processo de arranque da rede de transporte da REN, que começou no norte e avançou para sul.

O apagão propagou-se pelas redes móveis de Portugal, obrigando a medidas agressivas de poupança de energia, à medida que a procura de tráfego aumentava e as reservas de energia se esgotavam

Quando o colapso de toda a rede cortou a energia em praticamente todo o território português continental, às 11h33, hora local, do dia 28 de abril, as antenas móveis foram imediatamente desligadas da corrente elétrica principal e tiveram de recorrer a baterias ou geradores de reserva, desencadeando uma corrida nacional entre a restauração da rede e o esgotamento das reservas de energia nas redes de telecomunicações. As infraestruturas que não dispunham de qualquer autonomia energética desapareceram imediatamente (como as “small cells”— micro- e pico-células), desencadeando um colapso gradual da densidade global da rede que se assemelhou a uma queda abrupta seguida por uma diminuição gradual.

A súbita perda de eletricidade residencial tornou as redes fixas e os equipamentos de Wi-Fi domésticos (CPE) inutilizáveis, obrigando os utilizadores a recorrer às redes móveis e desencadeando um aumento massivo de tráfego que exerceu uma pressão intensa sobre a capacidade, em especial nas áreas urbanas. Isto refletiu-se numa rápida degradação do desempenho das redes móveis em todas as métricas, conforme ilustrado na análise dos dados Speedtest Intelligence® publicada na nossa investigação anterior.

O aumento súbito da procura na infraestrutura móvel do país ocorreu precisamente quando as operadoras estavam a correr para implementar medidas agressivas de poupança de energia para prolongar a duração da energia de reserva nos sites móveis. Esses esforços incluíram o desligamento faseado do 5G (já que os rádios MIMO de 3,5 GHz normalmente consomem duas a três vezes a potência de um setor 4G de baixa frequência), priorizando os principais serviços de voz e texto e reduzindo a potência de transmissão de ponta das células quando as cargas de rede eram baixas.

O apagão produziu uma curva de falha composta por um grande salto (DIGI) sobreposto a vários picos distintos (Vodafone, NOS e MEO)

Embora todos os operadores móveis em Portugal tenham implementado medidas semelhantes de poupança de energia durante o apagão, o grau e a distribuição da autonomia energética da infraestrutura de rede de cada operador, incluindo a infraestrutura parcialmente partilhada entre a NOS e a Vodafone, acabaram por moldar a resiliência das suas redes. Isso é evidente nas trajetórias distintas de falhas reveladas pela análise dos dados de monitorização passiva de sinal, que indicam se um dispositivo conseguia ligar-se a uma das redes (2G, 3G, 4G ou 5G), com base numa amostra ampla e geograficamente diversificada de todo o território português.

A rede ainda em fase inicial da DIGI, com uma cobertura mais limitada e fortemente concentrada em áreas urbanas (o que torna a implantação da autonomia de energia mais difícil em infraestruturas no topo de edifícios), revelou-se particularmente frágil. Quatro horas após o colapso da rede elétrica, a percentagem de assinantes da sua rede sem qualquer sinal disparou de menos de 0,1 % para mais de 90 %, um colapso abrupto e generalizado, típico de um corte súbito. Toda a infraestrutura de rádio da operadora parece ter desaparecido quase em simultâneo, impulsionada por baterias de curta duração ao nível dos sites e com pouca redundância em camadas superiores. Além disso, o acesso à rede permaneceu severamente comprometido por mais de um dia, apontando provavelmente para uma falha catastrófica de elementos mais profundos, como o Evolved Packet Core (EPC) em Lisboa, que pode ter carecido de redundância geográfica ou de autonomia energética suficiente.

Embora a curva de falhas da Vodafone não tenha apresentado o mesmo perfil de queda abrupto como a DIGI, seguindo mais uma forma triangular, ainda assim atingiu um pico muito acentuado. A distribuição heterogénea da autonomia energética na rede em toda a área de cobertura da Vodafone produziu uma curva de sobrevivência em várias etapas, com cada faixa de autonomia a esgotar-se (por exemplo, locais de rede com baterias de quatro horas) a provocar um novo ressalto visível na trajetória do apagão.

Por volta das 19h30, hora local, quase 70 % dos assinantes da Vodafone estavam sem serviço, à medida que as últimas reservas de energia de apoio começaram a esgotar-se antes do restabelecimento da rede elétrica. Embora este valor seja significativamente inferior aos mais de 90 % de perda de serviço verificados na rede da DIGI em Portugal, representava quase o dobro do pico de interrupção registado por qualquer operador em Espanha no dia 28 de abril. O serviço, contudo, foi rapidamente restabelecido na rede da Vodafone a partir das 20h00, seguindo uma sequência geográfica faseada, em consonância com a reposição da rede elétrica, com a taxa de ausência de serviço a cair para menos de 5 % à meia-noite.

Ao contrário de outros operadores em Portugal, a Vodafone e a NOS partilham extensivamente a RAN, uma joint venture que possui e opera infraestruturas partilhadas ativamente em áreas rurais e do interior, enquanto nas zonas urbanas as infraestruturas são partilhadas de forma passiva. Apesar disso, o perfil de interrupções da NOS foi notavelmente menos grave. Isto indica que a rede da NOS apresenta uma resiliência energética relativamente maior nos locais onde a sua infraestrutura não é ativamente partilhada, em comparação com os geridos de forma independente pela Vodafone. Na rede da NOS, a proporção de subscritores sem serviço atingiu um pico precoce de quase 30 %, assemelhando-se de perto ao perfil de impacto do operador mais afetado em Espanha, mantendo-se neste nível até a energia ser restabelecida.

Os méritos das reservas de baterias amplas e profundamente distribuídas na atenuação e no adiamento da curva de falhas (de forma semelhante às máscaras e vacinas na contenção da propagação de infeções durante uma pandemia) ficaram claramente demonstrados no caso da MEO. O pico da interrupção foi menor e a retoma mais rápida, com a proporção de assinantes sem serviço a atingir um pouco mais de 16 %, o melhor desempenho observado em toda a Península Ibérica no dia 28 de abril.

A experiência do apagão demonstra o papel da autonomia energética e da geo-redundância no reforço da resiliência da infraestrutura das telecomunicações face a choques externos

Quando a rede elétrica colapsou, todos os operadores portugueses tentaram a mesma primeira alavanca: desligar a camada de 5G, intensiva em consumo energético. Mas a partir daí, os caminhos divergiram. A extensão e a robustez da autonomia energética de cada operador (ao nível das infraestruturas) e o grau de geo-redundância (ao nível do núcleo), juntamente com a capacidade de cascatear camadas em bandas inferiores, limitar o tráfego e reconfigurar o espectro, ditaram quanto da sua rede permaneceu operacional, e durante quanto tempo, durante o apagão.

A acentuada assimetria nos impactos do apagão observada entre as bases de clientes dos diferentes operadores realça a necessidade urgente de reforçar as redes móveis e elevar todos os níveis da infraestrutura a um patamar mais robusto de resiliência, em antecipação a futuros eventos graves. Existe um consenso alargado, que se prevê que venha a ser consagrado no futuro Digital Networks Act (DNA) da Comissão Europeia, de que as redes de telecomunicações são infraestruturas críticas essenciais para o funcionamento da sociedade, e que mesmo interrupções breves do serviço podem rapidamente transformar-se em riscos sérios para a segurança pública.

Ookla retains ownership of this article including all of the intellectual property rights, data, content graphs and analysis. This article may not be quoted, reproduced, distributed or published for any commercial purpose without prior consent. Members of the press and others using the findings in this article for non-commercial purposes are welcome to publicly share and link to report information with attribution to Ookla.